For the blood

is the life force

The bond of consanguinity

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter finally delves into the central motif of this book: blood. Once again, we return to primordial roots, echoing the primal definition of the relationship to animal after the Deluge: "But flesh with the life... which is the blood, you shall not eat. And surely your blood of your lives will I require; at the hand of every beast will I require it, and at the hand of man; at the hand of every man's brother will I require the life of man." As in Genesis, humanity and animal are tied together in bonds of blood. Man is given rights of eat, but not to the life force.

Here, the limitations seems tighter. The opening verse seems to imply that any taking of animal life outside the context of the Dwelling borders on murder: "Any man of the house of Israel that kills an ox, or lamb or goat in the camp...and brings it not to the doorway of the Dwelling...blood shall be imputed to that man, he has shed blood". This supposition is contradicted by later references to hunting--the killing is allowed, but the blood must be treated with respect.

Life force/soul (nefesh) becomes embodied in blood. The river that ties together all life force, it also allows for atonement].

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 16

Inside

Outside

Between

The veils of concealment

of closeness

The moment in time

and what follows

[For full chapter, click here

After the various laws creating a correlation between human body and the Dwelling, we return to the death of the "two sons of Aaron". The leitwords are the same: "closeness" (k'r'v), "fire," "face/presence" (lifnei/ pnei). Yet this is a return that is informed by the laws that followed. Once again, a doubled sacrifice (an echo, perhaps, of the two lost sons?) that holds within it life and death--here, the scapegoat sent "out" deep into the desert. The focus is still inner and outer spaces (ve-yetze "to go out", "vayavo" "to come") and the liminal space between them--the "doorway" of the Dwelling becomes the "veil" setting apart the "holy of holies."

The ritual that allows for the very "coming close" that destroyed the two children of Aaron also distills and encapsulation the laws that introduce it. By clarifying the inner, the outer, and the liminal, it for the first time allows the Dwelling "to dwell with you within your impurity"--a contrast to the previous chapter's deadly "Let them not die in their impurity, when they make impure my Dwelling which is within them."

We also introduce a motif of time, a counterpoint to the emphasis on space: "any moment (et) he comes to the holy" "send it with a man of the moment (ish eti)"; an intimation of the future, where a different priest will serve "in the place of his father." Time seems to provide the missing link between the inner and outer spaces]

Friday, July 25, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 15

What is inside

seeping outside

extended circles

touching

Inner and outer temples

Contain yourself

[For full chapter, click here

We continue with the laws of tumah and Tahara, ritual purity and impurity, this time focusing on male and female bodily discharges, what "seeps" (zav) out of the body.

Again, the Temple-consecration pattern of seven-days-and-eighth-day-transition; again a duality (two birds in each of the offerings; male/ female; two categories of discharge ). And throughout, the focus on the tension between inner and outer spaces. The zav represents an inner space seeping outwards, contaminating in widening circles, an inversion of the "tent of meeting," whose holiness seeps from the center out. Once again, there seems a strange correlation between the human body and the Dwelling. The human spaces must be contained, in order for the tend to "dwell within you."]

Friday, July 18, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 14

Out In

Dead Live

Till the inner sanctum is destroyed

And you fly free over the field

[For full chapter, click here

The healing of the metzorah (loosely translated as "leper"). At last, he breaks out of the endless cycles of sevens, as he too reaches "the eighth day."

The ritual embodies duality: the living flesh, and the dead tzarrat lesion, the two birds--one slated for death, the other, marked in blood, set free to fly "over the face of the field"; two sheep.

The greatest tension is between inner and out--an echo of the "days of filling" consecrating the Dwelling, which also revolved around "going outside" and remaining in the "doorway." The chapter opens with the metzorah being "brought/ coming in" and the priest going out (ve-yatza). The metzorah must sit alone "outside" the camp; then can come "in." One bird of the offering is offered "within" the Dwelling, the other flies away outside. The spacial focus comes to the fore in the laws of house-tzarrat, in begins with parts of the inner dwellings cleared away to "outside" the camp, and closes with the complete destruction of teh houses' wall. the tzaraat experience somehow revolves around a redefinition of inner space)

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 13

See

Be seen

Make manifest

When did flesh

become you?

[For full chapter, click here

The world of the divine resonates throughout the human encampment, as the chapter continues to discuss the theme of human tumah and tahara (loosely translated as ritual purity and impurity) with the laws of tzaraat (a skin disfigurement sometimes identified as leprosy).

The key word is "seeing" and "eyes"--the root r'a'a (roe, mar'e, yirah-e) repeats over twenty times. This is a chapter of stripping away, removing what is covered, exposing rot.

The strange correlation between the human body and the Dwelling persists. We return to the primal language that opened the Book of Leviticus: "Adam," human, earth-creature, rather than the more conman "man"; followed by "nefesh," soul--mirroring the initial description of the Temple service. There is a focus on clothing--the defining characteristic of the priest. Interwoven is also the motif of fire and burning--an echo of the death of Nadav and Avihu "on the eighth day." Like the Dwelling, the skin lesion is defined through a seven day process of enclosure. But in contrast to the dedication of the Mishkan--and the purification of a woman after birth-- here, there is no concluding "eighth day", no transition between inside and out, no death and rebirth. Instead there is a trapping within a system of repeated cycles of sevens.

As the chapter enumerates the various ways of diagnosing the skin lesion, there is a continous interplay between the person and the flesh-disease. In the opening section, the subject is "adam"--the person; in the second section, the subject is "tzarrat" --the disease itself. In the closing, the person is defined by the disease. He is a metzorah, an embodiment of tzarrat. It is no longer the lesion that is "tameh--impure" but he. The person has becomes his flesh]

Leviticus: Chapter 12

The human dwelling

dedication

blood

small deaths

To hold multiplicity

[For full chapter, click here

From the laws of food and animals, we move seamlessly into the laws of human purity and impurity. There is a slippage of meaning, with the key words remaining the same, but changing context: tahor (kosher, pure) ta'me (not-kosher, impure); the plant seeds here become human gametes: "a woman who gives forth seed".

In this extension of the holiness of the Dwelling into the human realm, there is a strange confluence between birth and consecration; the woman's body and the Mishkan. Like the Mishkan, dedicated in a seven day ceremony that is completed "on the eighth day," the impurity after birth follows a seven day cycle followed by "on the eighth day". As in the case of the consecration of the Mishkan, the focus is on blood. Here too, there is a focus on duality and separations: the doubling of the days in the case of a female baby; the double offering brought at the end of the birth period.]

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 11

Divine and human eating

What is set aside

Division

and transition

What is touched

carried

ingested

Within flowing waters

[For full chapter, click here

Aaron's answer to Moses at the closing of the previous chapter triggers a change. He is now a subject rather than passive object; no longer spoken to, but one of the speakers.

After the "fire that came forth" to "eat" (ahal) the offerings and the two sons of Aaron, we move to human eating: what can be eaten, and what cannot. As in the previous chapter, the focus is on the specificity of appropriateness. "These are the things that are good for you" "they are unclean to you." All is defined by context; nothing is absolute.

The aftermath of the death of Nadav and Avihu continues to be havdala, differentiation. As in the previous chapter, the clearly demarcated spaces and merged by transitional limens. The priests who remain at the doorway here becomes the watery solvent that both doesn't become impure, but yet enables impurity. We differentiate between what enters the lips, ingested ; and what is carried outside the body]

What is set aside

Division

and transition

What is touched

carried

ingested

Within flowing waters

[For full chapter, click here

Aaron's answer to Moses at the closing of the previous chapter triggers a change. He is now a subject rather than passive object; no longer spoken to, but one of the speakers.

After the "fire that came forth" to "eat" (ahal) the offerings and the two sons of Aaron, we move to human eating: what can be eaten, and what cannot. As in the previous chapter, the focus is on the specificity of appropriateness. "These are the things that are good for you" "they are unclean to you." All is defined by context; nothing is absolute.

The aftermath of the death of Nadav and Avihu continues to be havdala, differentiation. As in the previous chapter, the clearly demarcated spaces and merged by transitional limens. The priests who remain at the doorway here becomes the watery solvent that both doesn't become impure, but yet enables impurity. We differentiate between what enters the lips, ingested ; and what is carried outside the body]

Monday, July 14, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 10

Come bring

and be consumed

the eating fire

the thin line

alien and belong

inside and out

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter continues seamlessly from the last, sharing all its key words: "fire", "closeness/offering" (the root k'r'v), "face" (pnei), "holy" (kodesh). But what a transformation. The hidden menace in the complete integration of kohen and altar comes into the open. The same fire that "came forth" to "consume the ascension offering on the altar" now "comes forth" to "consume them," killing the two sons of Aaron. Another key word enters: "die" temutrun. It is shocking--and yet feels inevitable. Moses "brought close" (hekriv) Aaron and his sons--the exact same language used for "bringing close" (hekriv) an offering (korban)--a pattern which is emphasized by Moses statement: "this is what God meant when he said I will be sanctified by those closest (bi-krovai) to Me." Aaron's remaining sons become notar, "left over"--the same language used to describe the leftovers of the meal offering.

The fact that the high priest is aligned with "the entire congregation" in regards to the sin offering takes on a new overtone. The priests stand at the "doorway" because they are the buffer. "Do not die, and on all the congregation He will be wroth." "Your brothers, the entire congregation of Israel" will "cry over the burning that God has burned." The two sons of Aaron become the embodiment of the sin offering of the nation. The priests are the altar, with all the danger that implies. The fire that was greeted with joy must now be mourned with the same intensity.

We return to the tension between closeness and distance that animated the entire creation of the Dwelling. Aaron's sons run to greet the divine fire with "alien fire," and are consumed by the very fire to which they respond. Now comes a splitting. "you must differentiate (lehavdil)." The dead and the living; inside and outside; the doorway between.]

and be consumed

the eating fire

the thin line

alien and belong

inside and out

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter continues seamlessly from the last, sharing all its key words: "fire", "closeness/offering" (the root k'r'v), "face" (pnei), "holy" (kodesh). But what a transformation. The hidden menace in the complete integration of kohen and altar comes into the open. The same fire that "came forth" to "consume the ascension offering on the altar" now "comes forth" to "consume them," killing the two sons of Aaron. Another key word enters: "die" temutrun. It is shocking--and yet feels inevitable. Moses "brought close" (hekriv) Aaron and his sons--the exact same language used for "bringing close" (hekriv) an offering (korban)--a pattern which is emphasized by Moses statement: "this is what God meant when he said I will be sanctified by those closest (bi-krovai) to Me." Aaron's remaining sons become notar, "left over"--the same language used to describe the leftovers of the meal offering.

The fact that the high priest is aligned with "the entire congregation" in regards to the sin offering takes on a new overtone. The priests stand at the "doorway" because they are the buffer. "Do not die, and on all the congregation He will be wroth." "Your brothers, the entire congregation of Israel" will "cry over the burning that God has burned." The two sons of Aaron become the embodiment of the sin offering of the nation. The priests are the altar, with all the danger that implies. The fire that was greeted with joy must now be mourned with the same intensity.

We return to the tension between closeness and distance that animated the entire creation of the Dwelling. Aaron's sons run to greet the divine fire with "alien fire," and are consumed by the very fire to which they respond. Now comes a splitting. "you must differentiate (lehavdil)." The dead and the living; inside and outside; the doorway between.]

Friday, July 11, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 9

On this day

Today

Come close

See and make seen

Fire flows forth

Burning blessing

[For full chapter, click here

"And it was on the eighth day"... After all the laws and preparation, the seven liminal "days of filling" we finally arrive back on the day of consecration that closed the Book of Exodus. After standing "in the doorway" Aaron at last "goes out," (vayetze) connecting the inner world of the sanctuary and the outer world of the people in a "blessing" which causes "a fire to go forth (vayetze) from God.

They leitwords are "close, to approach" (karev, korban), to see (vayar, veyeru), and "face" (pani, lifnim). This is a day of intimacy, and of God making Himself visible.

The priests continue to function as a living element of the Dwelling. They are the connecting pieces between the people and the altar, "coming close" (karev) to bring the offerings of closeness (korban). ]

Leviticus: Chapter 8

At the portal

Fill me

Dedicated in blood

Clothe me in glory

Atone and consecrate

Altar and man made one

[For full chapter, click here

The dedication. The link between kohen and dwelling becomes even more intense, as they are consecrated in a single ceremony. Aaron is dressed; the alter is consecrated; Aaron's children are dressed; both are consecrated with the oil and blood from the altar, so that priest and altar become a single unit. The priests here are utterly passive, dressed and moved by Moses--just another component of the many-faceted Dwelling. The offerings are measured by "the filling of their hands": they are the measurement of the altar.

As in the case of the sin offering, the kohen stands in for the nation as a whole, brought by "the entire congregation."

This time of dedication centers on the limen, placed between two worlds. "The whole nation" congregates "to the door"; Aaron and his sons are to be "at the doorway of the Dwelling for the Days of Filling." We are at the transitional stage]

Wednesday, July 9, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 7

Bound together

or cut off

Divine and human eating

That which you bring

becomes yours

[For full chapter, click here

This chapter expands and intensifies the themes of the previous chapter. The connection between kohen and offering becomes tighter. If in the previous chapter, the priests were given general rights to certain offerings, here an intense one on one relation is established between the offering and the priest that offers it: "The one who atones with it, to him it shall be" "The skin of the ascension offering shall go to the kohen who offered it, to him shall it be" "and the kohen who throws the blood of the sin offering it shall be".

Countering this intense bond between the priest and the offering is the threat of a broken bond to those who disrespect the offerings, to those who overstep the bounds of the holy: "and he shall be cut off (karet) from his people."

The sharing of the offering between the human and the divine is accompanied by limitations to protect the boundaries of the divine. The chapter closes with a reiteration of the prohibition of taking the blood or the fat--the two parts of the sacrifice consecrated for the altar. Those who do so shall be "cut off"]

Leviticus: Chapter 6

The eternal flame

The great consumer

Burning through the night

The great consumer

And his watchman

[For full chapter, click here

A reiteration of the laws of the offerings, but with a transformed ambiance. No longer is the focus the one sacrificer, "a soul which shall bring." Now the focus is on the offering itself: "This is the law (Torah) of the Ascension Offering" "This is the law (Torah) of the Sin Offering."

We have returned to the primal call to sacrifice in Genesis: the Binding (akeda) of Isaac. "Take now your son, your only son, whom you love, Isaac, and ascend him as an ascension offering". The root "to bind" (akod, mokda, tukad) is the key root, along with "fire" (esh) "law" (Torah) and "holy" (kadosh). We are in the world of the altar upon which "an eternal fire shall burn (tukad).. it shall not go out". The only human presence is that of the altar's watchmen, the priests, who must feed it every morning. The person who brings the offering has disappeared.]

Monday, July 7, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 5

What is known,

Hiding the revealedLosing the foundTaking what is not yours

The guilt of holding

What unknown

Hiding the revealedLosing the foundTaking what is not yours

The guilt of holding

[For full chapter, click here

From "sin" het/hatat we move to "guilt" asham. The consequence of sin (ve-asham) here becomes an object that can actually be offered to God: "And he shall bring his guilt to God for his sin."

The Asham offerings comes for a variety of seemingly unrelated issues--withholding testimony, becoming unknowingly ritually unclean, breaking an oath; misuse of consecrated property; misuse of others' property . An underlying motif is the tension between the hidden/lost and the revealed/found: taking control of something that is not in your sphere]

Sunday, July 6, 2014

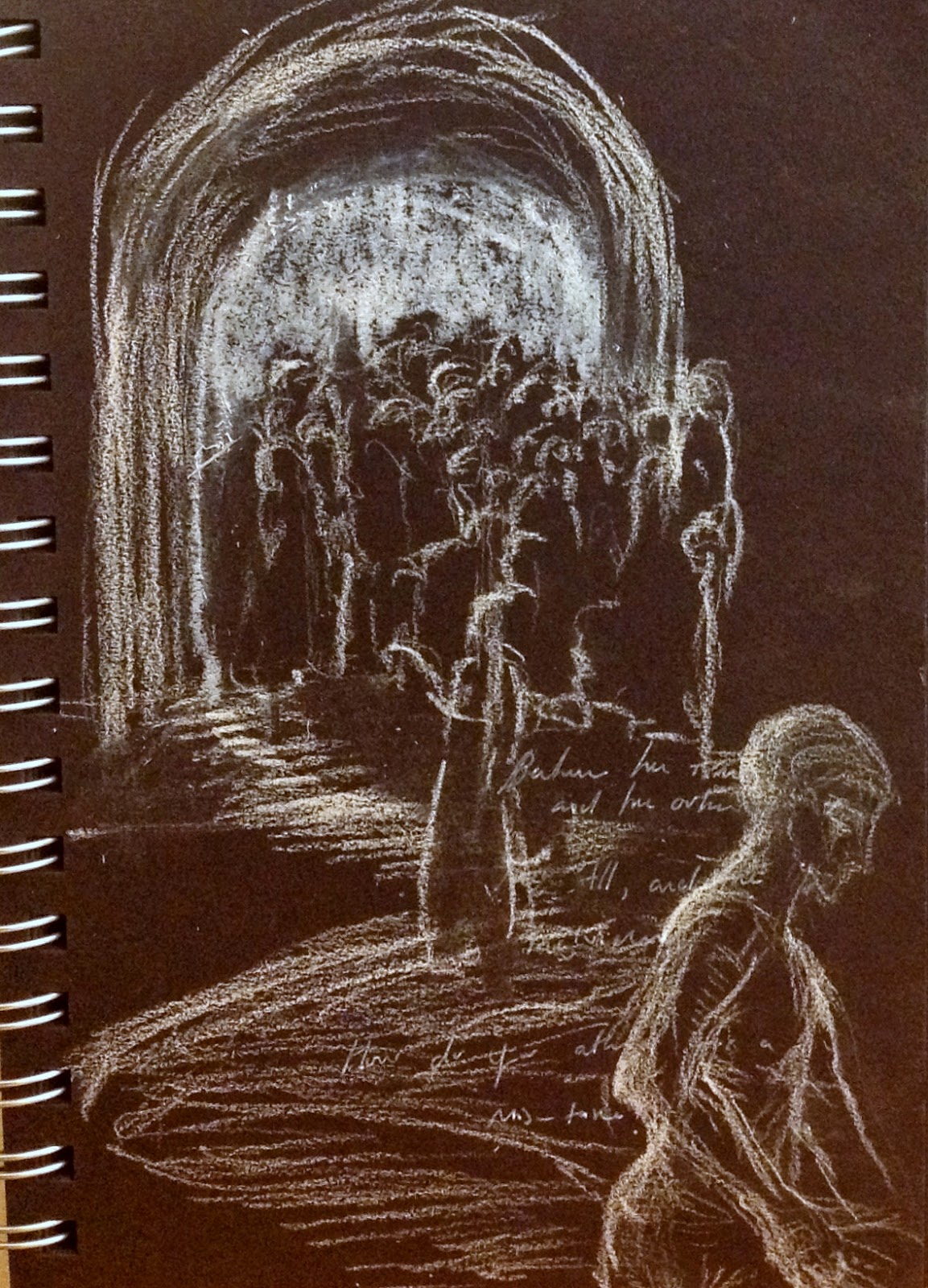

Leviticus: Chapter 4

Between the inner and the outer

The All, and the individual

How do you atone

for a mis-take?

[For full chapter, click here

Again, a change of ambiance. For the first time since the "call", we speak of sin, atonement, blame, rather than simply "coming close". Yet there is a consistent comparison to the zevakh shelamim, the "peace offering" that created a join "eating" for the human and divine. The space of atonement is also a shared space of "God's commands" and humanity's "doing--asa." This space is animated by a tension between the collective and the individual It begins with the high priest, humanity's representative within the Dwelling; then then moves to the collectiveklal/all/ congregation. Only then do we speak of individuals--the king (who is not seen as standing in for the people in the same way that the priest does) and any "nefesh / soul from the people of the land."

Paradoxically, the offerings of the collectives (the kohen, the people) are brought into the intimate space of the sanctuary, while the private offerings remain outside, in the courtyard. Yet it is only the individual offerings that create "the pleasing scent" of the earlier, voluntary offerings]

The All, and the individual

How do you atone

for a mis-take?

[For full chapter, click here

Again, a change of ambiance. For the first time since the "call", we speak of sin, atonement, blame, rather than simply "coming close". Yet there is a consistent comparison to the zevakh shelamim, the "peace offering" that created a join "eating" for the human and divine. The space of atonement is also a shared space of "God's commands" and humanity's "doing--asa." This space is animated by a tension between the collective and the individual It begins with the high priest, humanity's representative within the Dwelling; then then moves to the collectiveklal/all/ congregation. Only then do we speak of individuals--the king (who is not seen as standing in for the people in the same way that the priest does) and any "nefesh / soul from the people of the land."

Paradoxically, the offerings of the collectives (the kohen, the people) are brought into the intimate space of the sanctuary, while the private offerings remain outside, in the courtyard. Yet it is only the individual offerings that create "the pleasing scent" of the earlier, voluntary offerings]

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Leviticus: Chapter 3

Separations

bread and spirit

human and divine

the broken parts

Do not touch

the blood

the glistening milk

[For full chapter, click here

A return to the animal. Once again, a focus on choice (a repeated anaphoric conditional), and a return to the third person. Yet the greater intimacy of the grain offering "thou" has had an impact. No more is this offering completely for God. Now it is split between the human and the divine, some parts offered, some parts left for the offerer.

The split between God and man paradoxically creates a harsher ambiance. The focus on the chapter is on splitting. We break up the simple unity of the ascension offering, carving the animal to its pieces. Each type of animal is craved differently. Each highlights a different aspect of the offering: cattle is a "pleasing smell"; sheep are "a bread/food offering"; goats bring together this duality--a "bread/food offering" that is also "a pleasing smell." The offering itself becomes multifaceted. It can be both male or female. It is an offering/ korban for "coming close" (le-hakriv); it is a type of incense (le-haktir); it is a zevakh, a sacrifice, cognate of "altar", mizbeach.

In creating a shared "food" for the human and divine, the "peace offering" also introduces duality, and the need for limits. Certain things do not belong to the human realm, cannot be ingested. The primordial blood, and the glistening white fat ( helev, cognate and near synonym of halav, milk) are not to be touched. ]

bread and spirit

human and divine

the broken parts

Do not touch

the blood

the glistening milk

[For full chapter, click here

A return to the animal. Once again, a focus on choice (a repeated anaphoric conditional), and a return to the third person. Yet the greater intimacy of the grain offering "thou" has had an impact. No more is this offering completely for God. Now it is split between the human and the divine, some parts offered, some parts left for the offerer.

The split between God and man paradoxically creates a harsher ambiance. The focus on the chapter is on splitting. We break up the simple unity of the ascension offering, carving the animal to its pieces. Each type of animal is craved differently. Each highlights a different aspect of the offering: cattle is a "pleasing smell"; sheep are "a bread/food offering"; goats bring together this duality--a "bread/food offering" that is also "a pleasing smell." The offering itself becomes multifaceted. It can be both male or female. It is an offering/ korban for "coming close" (le-hakriv); it is a type of incense (le-haktir); it is a zevakh, a sacrifice, cognate of "altar", mizbeach.

In creating a shared "food" for the human and divine, the "peace offering" also introduces duality, and the need for limits. Certain things do not belong to the human realm, cannot be ingested. The primordial blood, and the glistening white fat ( helev, cognate and near synonym of halav, milk) are not to be touched. ]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)